Eugene Binder, Long Island City, NY, Fall 1998

Catalog essay

As the corporate entertainment world introduces greater levels of "virtuality" into films (Toy Story, Jurassic Park) and computer games (Myst, Tomb Raider II), many artists are headed in the opposite direction, toward a kind of a sublime indeterminacy. Blurred transmissions, imperfect copies, and other waste products of electronic and digital media are the model for this new aesthetic, which is both symbiotic to and aloof from the global information network.

The recent marriage of Hollywood and Silicon Valley has revived the age-old quest for what Norman Bryson calls the "essential copy"--the depiction of seamless reality that preoccupied artists from ancient Greece to the late 19th Century.(1) Instead of complex history paintings full of perfectly rendered figures, the goal of current software writers is to create moving tableaux in which the figures interact, cast realistic shadows, and accommodate changing light sources--all at the click of a mouse.

These discoveries take place within labor- and capital-intensive workplaces like Pixar and Industrial Light & Magic, where employees scramble to top previous levels of verisimilitude. Technical achievement, not humanistic speculation or doubt, is the prime concern in these high-tech factories. Artists, on the other hand, are as interested in the "why" of technology as the "how." Where special effects crews are building images using computer-generated skeletons and fractal outer skins, artists are breaking pictures down into critically nuanced, constituent parts. Increasingly they are gaining access to home equipment that enables unorthodox uses of technology.

In his essay "The Abject Romance of Low Resolution," David Humphrey explores this scavenger role of artists in depth, reminding us that between the bottom feeder and the high-end manufacturer lies a multitude of image producers, armed with cameras, photocopiers, video equipment, Adobe Photoshop, and other devices--each possessed of its own technological signature, instantly datable, and situated within a shifting economic hierarchy based on levels of resolution or "quality." (2) Pictures made with outmoded or inferior equipment linger as abject counterparts to the state-of-the-art, and are recyclable not just by artists but also the mass media themselves (for example, Super-8 film to give Coke commercials a Gen X look).

"Images are the end products of cultural life," Humphrey writes, by which he means not highly-prized commodities but "waste, mov[ing] down the promotional, entertainment, or information chute." Extending this body metaphor to current artistic practice, he makes a Freudian-style analysis of paintings by Gerhard Richter, Andy Warhol, and other artists working with low-resolution or degraded iconography. For example, he links Warhol's "entropic recycling of mass produced images" with the later Oxidation Paintings, which involved "piss[ing] directly onto the canvas to produce a corrosive image of the spill"--a connection (and reinterpretation of Pop) that would have been unlikely prior to the '90s. (3)

In the present exhibition, John Pomara's abstract photocopies make a similar connection between bodily abjection and technological entropy, fusing primal mark-making--the Ab-Excremental smear--with the blurry smudges of the photocopier. Images of found paint drips are moved around gesturally while the copier-camera is scanning, yielding an initial set of photocopies that are then cut apart, collaged, and photocopied again--making it difficult to distinguish in the finished images where the movement of paint ends and photographic trails begin. Arranged in a grid, these daubs suggest Muybridge studies, chromosome charts, or taxonomic groupings of radar blips.

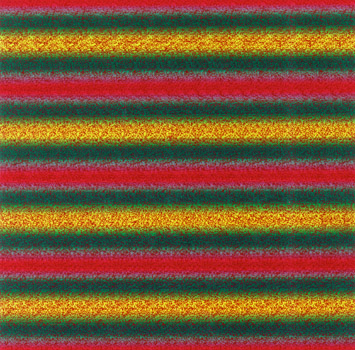

Tom Moody also works with photocopies, but instead of displaying them separately on the wall he tapes them together in slightly rumpled, quilt-like sheets. His computer-generated motifs, resembling electronic snow or TV test patterns, arise from a series of controlled accidents occurring at his clerical "day job." When he sends an image from the Paintbrush program on his computer to the network printer, the printer sends back a message announcing that the job is finished. This causes a power surge, and if he is sending another drawing to the printer at the exact same moment, the second image prints out as a uniquely garbled geometric scan pattern.  Moody makes multiple photocopies of the scan pattern and joins them in a grid, applying linen tape to the back of the paper. The finished piece is an idiosyncratic blend of Warholesque tiling, fabric design, and cargo-cult accumulation.

Moody makes multiple photocopies of the scan pattern and joins them in a grid, applying linen tape to the back of the paper. The finished piece is an idiosyncratic blend of Warholesque tiling, fabric design, and cargo-cult accumulation.

An interest in serial repetition and the creative use of electronic mistakes isn't just confined to the art world, it should be mentioned, but has also been a persistent theme in contemporary music. In the Appendix to this essay, Alexander Ross discusses the evolution of static in rock, ambient/industrial, and techno music, from the angry buzz of overdriven amplifiers in the '60s to sensuous, dreamlike textures in the '90s. Other important precedents are the Minimalists of the '60s, specifically LaMonte Young and Tony Conrad, whose amplified drones influenced the Velvet Underground and countless other bands. A tape piece from that period with great relevance to current visual practice is Steve Reich's "Come Out," originally composed as part of a benefit for six young men arrested for murder in the Harlem riots of 1964. As Reich explains:

"The voice [in the recording] is that of Daniel Hamm, then nineteen, describing a beating he took in the Harlem 28th precinct. The police were about to take the boys to be 'cleaned up' and were only taking those that were visibly bleeding. Since Hamm had no actual bleeding, he proceeded to squeeze open a bruise on his leg so he would be taken to the hospital--'I had to, like, open the bruise up and let some of the bruise blood come out to show them.'" (4)

The phrase "come out to show them" is played over and over on both channels, first in unison and then with one channel slowly moving ahead. As the voices go out of phase, a gradually increasing reverberation is heard which passes into a sort of canon or round. (5) Over the course of the piece's twelve minutes the words dissolve like cells whirled apart in a centrifuge, with individual phonemes--"om," "ou," "sh," and so on--settling into distinct strata consisting of vowel sounds (sustained humming) and consonants (a sibilant "whoosh"). What begins in a charged, political context becomes an edgy formal statement, "abstract" but suffused with political overtones.

A similar sifting and refining of loaded content takes place in the work of painter Carl Fudge. Explicit sexual imagery from a series of Japanese ukiyo-e prints is copied, broken down into grids, flipped symmetrically and asymmetrically, and repeatedly overlaid (using silkscreens) onto wood panels. In the resulting allover abstractions, kimonos, drapery, and body parts intertwine in a complex mesh recalling circuit diagrams and Pollock drip paintings. Like Reich, Fudge analytically parses an emotionally heated moment into constituent fragments, and yet (also like Reich) this process leads not to cognitive clarity but a charged, oceanic blur. In his most recent work--employing photographic negatives of his own silkscreens--Fudge abstracts his source imagery even further, obscuring the distinctive ukiyo-e line in a smudgy haze with a strangely crystalline feel.

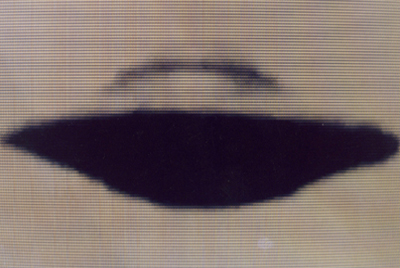

Claire Jervert's cibachrome photos also conjure a post-industrial sublime, but where Fudge slices and dices his source imagery by means of an elaborate private system (sometimes employing the computer, sometimes not), she organizes her "data" using a readymade grid--the phosphor dots of an ordinary television screen. Like Fudge, she transforms one type of peak experience into another, yet instead of sex, it's that popular paradigm of spiritual transcendence known as the "UFO sighting."  By photographing grainy images of flying saucers from '50s science fiction films and "documentary" sources directly off the picture tube, greatly enlarging them, and mounting them on sleek honeycomb aluminum panels, she transforms couch potato ephemera into high tech icons, with a suffused presence of mediated Rothkos.

By photographing grainy images of flying saucers from '50s science fiction films and "documentary" sources directly off the picture tube, greatly enlarging them, and mounting them on sleek honeycomb aluminum panels, she transforms couch potato ephemera into high tech icons, with a suffused presence of mediated Rothkos.

Where Fudge and Jervert process specific information into an evocative blur, David Szafranski begins with the blur and adds his data later. His medium is the "random dot stereogram" or "magic eye" illusion, which initially resembles a grainy field but slowly reveals optically encoded words as the viewer's eyes become acclimated to the pattern (not everyone can see them). Printed out in 2 X 2 foot squares and folded around stretchers, these seductive, two- and three-color fields look like abstract art, but once viewers learn they contain hidden messages, the artist says, "they'll look at them much longer than they would abstractions." (6) One seeking profound meaning in these voids may be disappointed, however, since the messages are generally pretty stupid. After gazing patiently at Grande la Creme de la Cuisse, 1995, for example, the viewer is rewarded with a glimpse of the words "thigh cream," while the would-be voyeur (or shopper) drawn to Bra Sale, 1998, is told to STOP STARING.

Gazing into the electronic ether in search of titillation is also a driving force behind Ray Rapp's video loop Porn0, 1986-98, a foray into "re-photography" (famously practiced by Richard Prince and Sherrie Levine), in which Rapp appropriates a ten-minute loop of softcore porn scrambled by the Picassos and de Koonings down at the local cable company. Their less-than-perfect encryption, ostensibly to protect children from witnessing the sex act, is actually the greatest possible advertising for the porn channels, since the glimpses of T & A combined with the viewer's prurient imagination makes the movies seem much sexier than than they are. In addition to the non-stop surrealism of squished faces and merged bodies, the scrambling process yields striking formal passages--e. g., stark white bands snaking through fields of blue sky and bare flesh.

Static Variations I, 1998, compiles bits of static and camera/VCR feedback generated accidentally and saved while Rapp is working on other video projects.  Intriguing in their own right as electronic abstractions, these rolling raster lines and stroboscopic flashes share affinities with Moody's computer glitches, Pomara's xerographic trails, and Jervert's out-of-focus TV sampling. With Szafranski's work nearby, one might be inclined to search these mysterious patterns for deep or conspiratorial meanings a la The X-Files, but so far as we know, the only alien technology generating these signals is our own.

Intriguing in their own right as electronic abstractions, these rolling raster lines and stroboscopic flashes share affinities with Moody's computer glitches, Pomara's xerographic trails, and Jervert's out-of-focus TV sampling. With Szafranski's work nearby, one might be inclined to search these mysterious patterns for deep or conspiratorial meanings a la The X-Files, but so far as we know, the only alien technology generating these signals is our own.

Where the multinationals are trapped in an addictive cycle of image-making that requires more and more "memory," artists, glutted with the refuse of the entertainment state, seem to be trying hard to forget. One might ask why so much recent work is diffuse, emptied-out, "abstract." According to Humphrey:

"The way an image copied or magnified many times breaks down into chaotic nonsense resembles the relation of figure and ground that Clement Greenberg saw as the structural grammar of Modernist painting. This relation could be considered a symbolic elaboration of the process of primary ego-differentiation. The struggle between a desire to lose one's boundaries and fearfulness of this loss, the promise of fulfillment and threat of dissolution, is the painter's romance of a return to origins, as well as the drama of degrading reproduction." (7)

Cheryl Edwards, Fall 1998

NOTES

1. See Norman Bryson, Vision and Painting (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1983). A concern predominantly of painters, the search for the Essential Copy trailed off with the invention of photography but has arguably been revived with the advent of computer animation.

2. David Humphrey, "The Abject Romance of Low Resolution," Lusitania Vol. 1, No. 4 (New York: Lusitania Press), pages 155-159 (cited as "Humphrey").

3. Humphrey, page 157. Another example might be Sigmar Polke, whose paintings weave together dissolving Ben Day dot patterns and organic, "alchemical" fluids.

4. Steve Reich, liner notes for LP Music of Our Time: New Sounds in Electronic Music (Columbia Odyssey, New York)

5. Ibid.

6. Email from T. Moody, quoting D. Szafranski, October 1997.

7. Humphrey, page 158. The quoted passage concerns the painter Jacqueline Humphries.

APPENDIX: The Recent History of Static in Recorded Music

by Alexander Ross

The static trend in rock music grew initially out of the fuzz guitar sound (best known from the Rolling Stones' "[I Can't Get No] Satisfaction"), which imitated an over-driven or distorting amplifier. Hard-rock outfits continued to push the "guitar wall of sound" well after the '60s, refining it into a subtle and controlled art.

The creative fringe took interest in an accidental by-product of this distortion: the overtones of fuzz, a warm "pink noise" (white noise is static without tone, pink noise is static or "snow" with a hum, or discernible pitch) that rode seemingly independently on top of the music. An early exploration of this might be Eno's "Needle in the Camel's Eye" from 1973, where the constant smashing of guitar chords creates a wall of wavering noise above the song.

A foundational work appeared in the mid-'70s with Lou Reed's controversial and fan-disappointing double LP Metal Machine Music, an all-static-and-feedback statement that figures in rock history much the way Futurist noise performances function in the history of theatre: pure, unequivocal rebellion.

There were some notable static undergrounds coming along in the late '70s/early 80's, namely Chrome (out of San Francisco), and a little later Fi (pronounced "eff eye"). Throbbing Gristle might also be mentioned here, as well as This Heat and Cabaret Voltaire (for example, "No Escape" off their classic first release, Mix-Up). The first group to make the intentional breakthrough into pure static would have to be The Jesus & Mary Chain, who eq-ed the bass-end off the fuzz chords entirely, leaving a shrill, static constant running relentlessly throughout their songs. Next would be Kevin Shields of My Bloody Valentine, where the static becomes more textured and smeared, literally permeating the music. The effect is a sexy, dreamlike blur echoing early '90s trends in fashion photography. Static finally becomes the main subject with the rise of Flying Saucer Attack (Chorus is a good example), out of Virginia, of all places. Here the static is totally frontal, and the music sort of whispers at you through a snowy haze.

The advent of the compact disc in all its sterile flawlessness brought about the realization that technological defects such as tape hiss, amp buzz, record groove ticks, and ultimately the computerized glitches sometimes heard on the CD itself were now interesting sounds never before utilized in conjunction with music. This, combined with the inexpensive home recording boom, coalesced into what became known as LO-FI. Major players, largely confined to the US and New Zealand, include Lou Barlow/Sentridoh, Daniel Johnston, Guided By Voices, and (from New Zealand) post-rockers The Dead C and This Kind of Punishment.

Mid-'90s developments quickly cross-over into the techno-ambient realms with Oval, who boldly dominate the glitch and hiss scene. Mention should be made of Scanner, an individual who scans cell phone conversations and create pieces out of them, with the natural static of the transmission wavering in and out. Most recently is Porter Ricks, also techno-ambient, whose distant discotheque is heard pleasantly through walls of dreamy smush.

The ambient/industrial sector was long-ago onto the static phenomenon, but here there is no music at all, just pure, wonderful noise. Examples here would be The Hafler Trio, Arcane Device, Tibetan Red, PBK, and early Nocturnal Emissions.

Photos, top of page to bottom:

Installation view, left to right: David Szafranski, Bra Sale, 1998, ink on paper; Ray Rapp, Feedback, 1998, VHS tape; Tom Moody, Surge Drawing (Green), 1998, photocopies, joined with linen tape and folded around 30 x 30 inch wood stretcher

David Szafranski, I'm PG, 1998, ink on paper (not in exhibition)

Tom Moody, enlarged view of Surge Drawing (Green)

Claire Jervert, "3"/1998OZ-1, 1998, cibachrome on aluminum honeycomb

Ray Rapp, Feedback, 1998 (only one monitor used in exhibition)

Installation view (photo taken during installation), left to right: Carl Fudge; Claire Jervert, "3"/1998OZ-1; John Pomara,Track and Field, 1997, photocopies (45 elements), 8 1/2" X 11" each