Tom Moody, December 9, 2002

Tom Moody, December 9, 2002

Reviews of the film One Hour Photo (no longer in theatres but due out on DVD soon) concentrated on its stalker theme and its critique-of-suburbia theme but pretty much left its art theme the hell alone. (Caution: this discussion reveals plot points.) Charles Taylor, in an incredibly obtuse write-up in Salon.com, called the movie “art house horror” but only used the word “art” as a tossed-off insult in the course of demolishing it on more typical (dramatic, cinematographic) grounds. (FN1) He never considered whether the filmmakers might be interested not just in the “art house,” but art itself, and overlooked another fair reading of the movie: that it’s a parable of creative regeneration told under the guise of a psycho-slasher film (a parable only half-interesting, but more on that below).

The movie is of two minds about its protagonist, moto-photo manager Sy Parrish (played by Robin Williams). On the one hand it presents him as a nerdy, sexually repressed freak--that’s clearly how the police and other characters see him. The main narrative arc tracks his slow progress towards psychological breakdown: you know it's coming, just not when or how. Yet on the subtext level--a story told visually but never in words--the film also suggests he’s a latent artist, and the meltdown triggers a change in the (unconscious) direction of his "work." Because this personal paradigm-shift is gained at the expense of others’ trauma, it might seem crass or irresponsible to give Sy’s activities any credence; let’s proceed on the assumption that people can be brawlers (Caravaggio) or total reclusive nutjobs (Henry Darger) and still make something worth thinking about.

At the beginning of the film we learn about Sy’s project (again--it’s never explicitly presented as such) in a way clearly meant to provoke shock. In his position as manager of a suburban photo lab, he has for many years been secretly collecting snapshots of a particular family--an attractive couple called the Yorkins, who have a small boy. On one wall of his mostly empty apartment, he has arranged the photos in a gigantic floor to ceiling grid, dramatically lit with photographer's lights on tripods. Sy tells us, in voiceover narration, that the photos only show the side of the Yorkins that they want the world to see--bland smiling moments of birthday parties, vacations, etc. So why collect the damn things? The movie suggests it is a form of wish fulfillment, a means of acquiring the perfect family Sy never had.

We’re meant to assume that Sy arrived at the photo-panorama innocent of all artistic precedent. Yet its trappings suggest a sophistication all out of proportion to the usual crude pushpinning of cinematic bedroom shrines. The neat, trim grid of photos is a staple of conceptual art, practiced at one time or another by the hundreds of artists since the ‘60s, famously including Sol LeWitt, Hanne Darboven, and more recently the cross-dressing performance artist Hunter Reynolds (although the latter‘s stitched-together photos actually spill onto the floor). Using tripods to light the grid recalls William De Lottie's presentation of fabric swatches and Xerox prints in the 2000 Whitney Biennial--a gesture of pure, gratuitous theatricality.

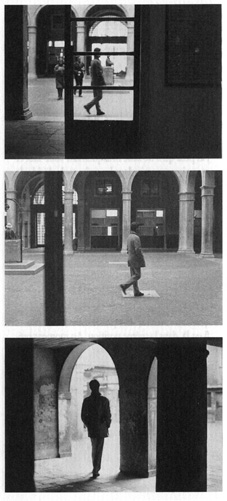

Even stalking has its proponents in the art world. Early in her career, the French conceptualist Sophie Calle picked people at random and covertly followed them around, documenting their lives with photos and texts (see, for example, Venetian Suite, 1980). Her work is controversial because of its invasion-of-privacy issues. At what point does artistic freedom trump the individual's right to be left alone? (Most people would say never, yet Calle is hanging in major museums.) Sy's project, were it real, would actually be more obsessive than Calle's, in that it stretches on for years rather than months, incorporating major life events into its tableau (marriage, first child, and, as it turns out, infidelity and estrangement). In its sheer longevity it recalls Mary Kelly's Post Partum Document, a years-long documentation of the birth and early child-rearing of the artist's son.

Whether Sy’s big photo grid is an unconscious channeling of ideas from the gallery and museum world, or just the filmmakers’ attempt to inject some conceptual art style into the mise en scene, the “piece” is ultimately derivative, and a bore. As Sy himself suggests, the project gives us no insight into the Yorkins, and physically it employs familiar strategies. Yet on the level of artistic parable, a key moment in the film occurs when Sy discovers a group of photos taken by the Yorkins' young son. These are very abstract shots of toys and other items from the child's room, photographed in vivid color and oddly cropped. When Sy opens the envelope containing the pictures, he sits down on the floor of the photo lab and studies them, obviously deeply moved. On the narrative, moving-the-story-forward level, it's because Sy is lonely man, loves the kid, and worships everything he's done. However, a glimpse of the photos over his shoulder reveals that they’re actually rather good, combining a William Eggleston-like vernacular formalism with the herky jerky “snapshot aesthetic” of Wolfgang Tillmans and the like. Once again, because a sophisticated art director has stepped in, it’s possible to interpret Sy’s reaction to the photos as disinterested aesthetic pleasure: that he’s moved not just by the child, but by the freshness and randomness of the child's vision.

At the beginning of the film, we see Sy in police custody, repeatedly asking to see "his photos." In flashback we learn of his unhealthy attachment to the Yorkins, and watch him cross the line when he learns that the husband has been cheating (through an indiscreet roll of film dropped off at the photo lab by the man's mistress). In Sy's anger at learning that his perfect, adopted family has flaws, he freaks, and in the film's most excruciating scene, goes to the lovers’ hotel trysting spot and, at knifepoint, takes pictures of them performing simulated sex acts in the nude. The film's supposed big revelation is that Sy was an abused child, apparently forced to pose for k1ddie p0rn by evil parents; the photo-taking is an unconscious acting-out of the earlier cruelty.

The film ends with another twist, though. The audience assumes that the photos he keeps asking for in the interrogation room are his shots of the husband and girlfriend. Turns out they're photos he took in a nearby hotel room, before the police found him, on a separate roll of film. When a sympathetic cop finally hands them over, Sy patiently lays them out on the table and we can see they're images of the sofa, clothes hangers, bathroom fixtures, and the like, shot at odd angles and strangely cropped. He seems quite content looking at them.

Again, the movie is very ambiguous about Sy. We could take these non-photos as a sign of his ultimate derangement, except that they're very reminiscent of the boy's pictures we saw earlier. There's a tradition and an appreciation of that type of photo in the art world, from Joseph Cornell films to Tillmans' scatter installations. Thus, in subtext, the movie suggests that Sy's personal crisis forces an artistic breakthrough: that he goes from being fixated on a family--or his need for a family less horrific than his own--to the beginnings of a personal vision, guided by the guileless creativity of a child.

If that is in fact the subtext it's a sentimental idea of a breakthrough, and also conservative, implicitly suggesting that stealing photos from the lab and making art out of them is “unhealthy” but taking “your own” pics isn’t. I'd argue that, quite the contrary, dweeby little Sy could potentially be the Jimi Hendrix of conceptual photography, with that big, sleek, high tech (but still analog/retro) photo processing machine as his ax. Obviously he loves it--in the film we see him cleaning it, tweaking settings, and calibrating chemical levels to get perfect color balance. The tantrum he throws when the philistine AGFA repairman refuses to shift the blue a few notches is the snit of a pure, driven poet, who isn't getting the effects he wants. Yet up until now he's had no eye, only obsession.

Quietly hunkered down in suburbia, making the most of The Man's equipment, Sy could represent a new breed of artist, leaving the public realm of portraits and Sistine ceilings and going deep underground, into the belly of the industrial/consumer capitalist machine. Again, this is not without precedent in the art world. In the 1995 exhibition "Other Rooms," at Ronald Feldman gallery in New York, the Brooklyn space Four Walls organized an entire exhibit around the "art of the day job," featuring dozens of works made in (or about) publishing companies, ad agencies, video editing facilities, and stock photography boutiques: all places artists have gone to earn a buck and ended up finding content.

The most heartbreaking moment in the film isn’t when Sy confesses that he was an abused child, but when his boss detects his petty pilfering, summons him into the office, and cans him. (This is another catalyst leading to his breakdown.) All artists who've ever borrowed supplies, equipment, or images from a job likely had hearts in throats during that scene. But even with a job, Sy lacks a good subject, and that’s where the Yorkin boy comes in. If, as the film suggests, the kid has opened Sy’s eyes to the wealth of abstract, vernacular, quirkily personal images flooding across his countertop, all Sy has to do is cull them with his practiced eye and he’s going to rule as an artist. Why take your own photos when there are millions waiting to be recontextualized? Sy's grid (or whatever configuration it ends up being) can now finally start to be interesting, assuming, that is, he can find another lab job once he gets out of the slammer.

FN1. As evidence of the film's "artiness" Taylor obsessed about the sterile squeaky-clean interior of the Walmart-type store where much of the action takes place, blasting it as a caricature that condescends to the American middle class. Yet Jim Hoberman in the Village Voice was much more perceptive in recognizing that this interior, like the film's Danish-modern police headquarters (and having the cops working for something called the “Office of Threat Management") were among its many subtle, almost science fictional elements. Other critics suggested that the slickness of the "Walmart" reflected the protagonist's deluded POV; still others recognized the interiors as Kubrick-land and let it go at that.