Alex on Film continues to tolerate my comments -- here are some more discussion threads:

The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

Playtime (1967)

American Sniper (2014)

Black Hawk Down (2001)

The Terror (1963)

The Man with the Iron Fists 2 (2015)

Alex on Film continues to tolerate my comments -- here are some more discussion threads:

The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

Playtime (1967)

American Sniper (2014)

Black Hawk Down (2001)

The Terror (1963)

The Man with the Iron Fists 2 (2015)

Adding things to a blogroll is so 2004, but regardless, I recently found The Dwrayger Dungeon, which takes screenshots of great crap movies and tv shows (mostly of the psychotronic variety) and arranges the shots in top-to-bottom narratives, with captions channeling the style of an enthusiastic 13-year-old circa 1962. Here's an example, chosen at random, from a post on the classic Mexican horror film The Witch's Mirror:

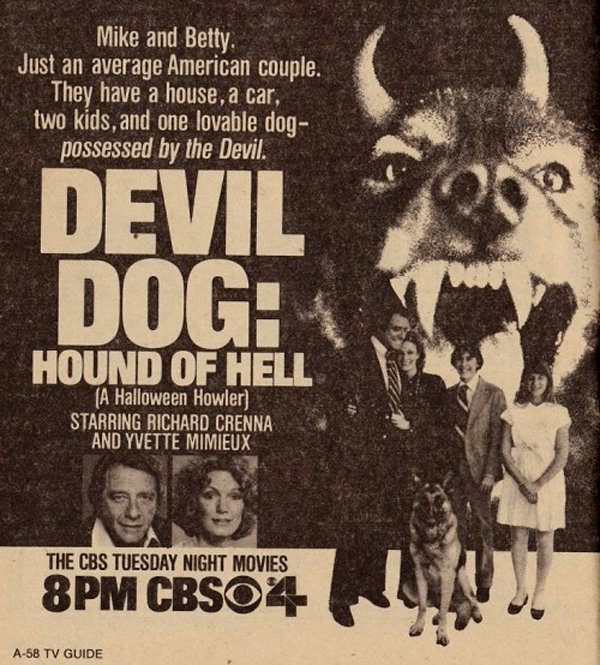

The poster below isn't from one of those narratives, but rather a collection of DVD covers and magazine ads for 1970s made-for-tv movies that would have been lost to the mists of time were it not for sites like The Dwrayger Dungeon:

woof woof -- ruff ruff -- scratches -- gnaws on bone in corner

Slacker (1991) was Richard Linklater's first film and still his best. Discussion of it tends to center on its role in defining "Gen X," the American youth-type that came between Boomers and Millennials. Yet it's a product of Linklater's mind: he wrote the words, rounded up unknowns of a certain age to speak them, and filmed them ingeniously. In some ways Slacker embodies every group of American 20-somethings who came out of college liberal arts programs, took a look at their employment opportunities (nonexistent or soul-deadening) and didn't want to leave the house (or communal house). In other ways, it partakes of the special chemistry of Austin, TX around 1990. Slightly run-down, cheap to live in, students everywhere, as well as an assortment of old, weird, human relics from the hippie '60s still visible in the streets. The monologue at the end about a "weapons giveaway program" is a verbatim rant from Jim Roche's Learning to Count, from the early '70s. Linklater didn't write it but he channeled it, especially its hostility. Slacker is funny but also angry; when people aren't delivering monologues to no one, they are bickering. The blog Alex on Film covered the movie last year, and I chimed in recently in the comments. Below are some excerpts from the post and comments.

Alex Good (from the main post): Mostly, the slackers are students. The few who most obviously aren’t are either old men or criminals. But what are they students of? I don’t think they’re MBAs or in law or med school. They’re not engineers or science majors. Instead, the sad joke is that they’re what had become, by the 1980s, the ring of scum around the university bathtub. They are students of the arts and humanities. Their interests are music, literature, film, history, and philosophy. Which means they have no role at all to play in modern life.

This is why they seem so adrift. While perhaps not lazy (a charge Linklater fiercely resists), they clearly aren’t getting much done. Hence the refrain we hear throughout the film of people being asked what they are up to and them saying “nothing much” or “um, nothing.” One of them has a band practice in another five hours, so . . . there’s the rest of the day shot.

But they are more lost than even this implies. They are a hundred performers in search of an audience. As Linklater sits in the back seat of the cab he drones on about alternate realities while the cabbie is clearly paying no attention to him at all. This encounter becomes the model for almost all the subsequent engagements. Even the band at the end is playing to an empty club. As Linklater points out in his commentary over this scene, most dialogue is a conversation and involves interaction but “this movie is very one-sided.”

Tom Moody (from the comments): Slacker is somewhat unique to Austin, Texas, in that it was a town where people could “drift,” from say, the ’60s to the ’90s. Texas conservative types were calling it the land of the lotus eaters decades ago. The University of Texas has a huge student population — 40,000 or so — and many graduates chose to hang around, because Austin was a relaxed and pleasant environment (it has since become more silicon valley/yuppie/materialist). Slacker is kind of the down side of all that hanging out. At the time I saw it, I took it as a black comedy — or what we’d now called cringe comedy — of/for stoner intellectuals. It is depressing, but that made it funny. [...]

You’ve made a good observation that these are likely mostly humanities students, and not engineers or business graduates. Since the 1970s, in the US, there is an awkward period for such students, where they haven’t found their “paying job” or “day job” yet and are just getting by from day to day, wondering what it all means (with agonizing self awareness from having just read Sartre and Joyce in school). Eventually the money runs out and they become nurses or paralegals, go back to school for a professional degree, start a meth lab, or what have you. Some will launch zines (then), blogs (2000s) or a twitter account (2010s) and may actually build an audience. In Linklater’s case he raised money and made a film.

In Slacker, because it was Austin in 1990 and relatively easy to live comfortably, you had a larger mass of these artistically sensitive people together in one place, with possible role models being the older anarchists and criminals you also have noted. (Austin at that time had a population of “dragworms,” which were homeless ex-hippies panhandling along Guadalupe Street, aka The Drag.) What makes the movie difficult is the tone of simmering hostility throughout. Couples bicker and bemoan that “humans need to be unhappy.” The woman handing out Zen “oblique strategies” cards has a shiner on her eye from domestic violence. There is a lot of petty theft happening (“2 for 1 special?”) The partying-with-camera at the end badly needs a killer from the woods to end the vacuous revels. Linklater’s upbeat statements, which you’ve quoted, should probably be discounted. Clearly, at the time he made this, he was pissed off about living in post-Reagan America and sick of his peers. The anger wasn’t necessarily generational, although Douglas Coupland’s book had a similar world-weary tone (from the excerpts I’ve read).

Alex Good (from the comments): Do you think he was that negative about these people? It’s interesting that because it’s so much a film of its time and place, his attitude and our attitudes have probably changed a lot with perspective. I mean, personally I can identify somewhat with some of the slackers (at least the less successful or likeable ones). I was a bit like this at this particular time. So if I’d seen this movie in ’91 (which I didn’t, at least that I recall) I think I would have had a different reaction to it than I have today, especially since I’ve seen what happened to this generation and also seen their replacements (the hipsters and the digital natives). I think Linklater probably feels differently today as well. At the end of the day, I think I feel more sorry for them than anything. I don’t enjoy their vacuous revels, but that killer was waiting in the woods for most of them.

Tom Moody (from the comments): I saw it in the theatre when it came out and clearly remember it, as well as my reactions, and the reactions of my friends (both boomer and gen-x). A boomer who had run a bookstore in the ’60s called Grok Books found it incredibly dismal (“where is the hope and sense of purpose that I felt at that age?” she asked). My gen-x friends found it amusing. Having suffered firsthand through the “yuppie” era I was glad to note a cultural shift from faux-’50s, morning-in-america sweetness to something more like the cynicism of the ’70s.

The film came out during the Bush recession and the standard media narrative (now) is that these slackers of 1990 became the dotcom millionaires of the Clinton era. Certainly a few did.

As for Linklater’s negativity towards his characters, you have the guy going to get coffee in his bathrobe (shades of Dude Lebowski). He thoughtlessly picks up the newspaper the paranoid guy is reading, walks back to his apartment with it, and cold shoulders his girlfriend, who wants to go out to a park and play frisbee. He starts showing interest, but only sexually, and she cuts him off by saying “that’s something I can do better myself.”* It’s a funny moment but dark. Why is he such a jerk? Is belittling his sexuality the answer? Dozens of these little moments have a way of adding up to a cumulative malaise — contempt not just for the world of the slackers, but the slackers themselves. As I noted, the negativity was refreshing after Tom Cruise and sunny Reagan fakeness but it makes for a tough emotional go, then and now. If viewers “dislike the people in it” (as you noted) that’s on Linklater, not “a generation.”

*The actual line is "No, no, no -- that's one thing that would be more effective on my own."

Alex Good (from the comments): Ouch! Is the standard narrative now that the slackers turned into dotcom millionaires? That’s even worse than the hippies selling out. Seems so unfair.

You’ve got an interesting take on the film. Darker than mine. I just had the sense that everyone is ignoring the slackers and in some of the worst cases maybe it’s made them bitter. But overall they seem paradoxically extroverted and withdrawn. Sort of manic. Perhaps today they’d all be taking medication.

Afterthoughts: It's a sign of Linklater's talent that people treat Slacker as if it were a documentary and not a one-man show with a hundred puppet performers speaking his lines. The narrative structure recalls Bunuel's The Phantom of Liberty, where a peripheral actor in one scene walks out and becomes the main actor in the next. Phantom's a dream film, about as far from the documentary form as can be. And yet, people read Slacker for what it says about a generation, not as a collection of routines and riffs by an adept film comedian.

In the film Gaslight (1944), Charles Boyer plays tricks on his wife (Ingrid Bergman) to make her think she is crazy, so he can have her committed to an asylum and find some jewels hidden in her house. Alex Good, at Alex on Film, prefers the less-well-known 1940 version:

In 1944 MGM managed to get a bunch of stars in alignment (and it wasn’t easy), but I prefer Anton Walbrook [in the 1940 film] to Charles Boyer. Walbrook is a more believable and altogether nastier piece of work. His creepy voice has an unnerving way of making his lines sound a bit like perverted baby-talk. And while it will be accounted heresy by some, I think Diana Wynyard is more convincing in the role of the bride coming unglued than the always composed Ingrid Bergman. Wynyard has the haunted, neurotic look of Véra Clouzot in Les Diaboliques, or Mia Farrow in Rosemary’s Baby. Finally, the amateur sleuth/hostler Frank Pettingell is a lot more fun than Joseph Cotten (“Saucy shirt, isn’t it?”), and Cathleen Cordell is a more erotic housemaid than Angela Lansbury, without having to try so hard. There’s some real heat generated between her and her louche master.

In the comments we discuss the term "gaslighting." The Maddow mafia evidently thinks Trump invented it but it was slung around quite a bit in the Bush II era. Good notes that Maureen Dowd even applied it to Bill Clinton, in the 1990s. How long has the verb "to gaslight" been around? One article traces it as far back as the 1960s TV show Gomer Pyle USMC:

Here’s an example of the verb “gaslight” in “The Grudge Match,” an episode that aired on 12 Nov. 1965 (antedating OED’s 1969 cite for the verb, as well as the Dec. 1965 cite for the verbal noun).

Duke: You know, you guys, I’m wondering. Maybe if we can’t get through to the sarge we can get through to the chief.

Frankie: How do you mean?…

Duke: The old war on nerves. We’ll gaslight him.

In addition to being a hoary cliche of political discussion, "gaslighting" has also been embraced by the therapy community. Search the term and you'll pull up many articles with titles such as "12 Signs You Are Being Gaslighted by a Narcissist." (Shouldn't that be gaslit?)

But for all its cliche-dom, repetition, and use as a Trump-cudgel, what does the term even mean? Politically, it seems to have devolved from “employing elaborate ruses to make a person think he or she is crazy” to merely “scaring people or psych-ing them out.” As a therapy trope its connection to the film(s) is tenuous. Most spouse abuse is not predicated on a calculated program of deceptions for material gain, it's just the guy being an a-hole. Both the pundits and the shrinks make the term mean what they want it to mean. They are, y'know, gaslighting us.

Alex on Film continues to tolerate my comments -- here are some more discussion threads:

Groundhog Day (1993)

Edge of Tomorrow (2014)

Point of No Return (1993)

Nashville (1975)

A Shock to the System (1990)

The Taking of Pelham One Two Three (1974)

Poltergeist (1982)

Conan the Barbarian (1982)

Long Weekend (1978)

Gaslight (1940)